The proposed aid package would mostly benefit civilian institutions over “drug war” priorities. Here’s how it breaks down:

On February 2, the State Department sent to Congress more details about its big request for US$1 billion in 2016 assistance to Central America, as part of next year’s foreign aid budget proposal. Compared to 2014, this $1 billion package would mean a tripling of foreign aid budget assistance to the region, especially to the three “Northern Triangle” countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras), which suffer very high violent crime levels.

The proposed new aid comes in response to the 2014 wave of unaccompanied minors fleeing violence from their home countries, in which 51,705 children from the Northern Triangle region, and 61,334 members of families with children, crossed the U.S. border.

The document submitted to Congress this week looks like a great improvement over past big U.S. aid packages to Latin America, which directed the vast majority of assistance to military and police forces, and which prioritized drug interdiction and the drug war over strengthening public security institutions. That was the case with “Plan Colombia” (2000–2006, 81 percent military/police aid) and the initial years of the “Mérida Initiative” for Mexico (2008–2010, 78 percent).

The majority of the aid in this proposal—at least 80 percent—goes to civilian institutions, civil society, and economic development, in recognition of the need to address the root causes underlying the violence and lack of opportunity driving migration. Further details about the aid will certainly reveal this to be a less-than-perfect package, but in broad strokes it represents an important shift: it seeks to address the full range of causes, instead of treating security cooperation as the central element. It recognizes that many institutions must be strengthened if Central America’s Northern Triangle countries are truly to protect their citizens.

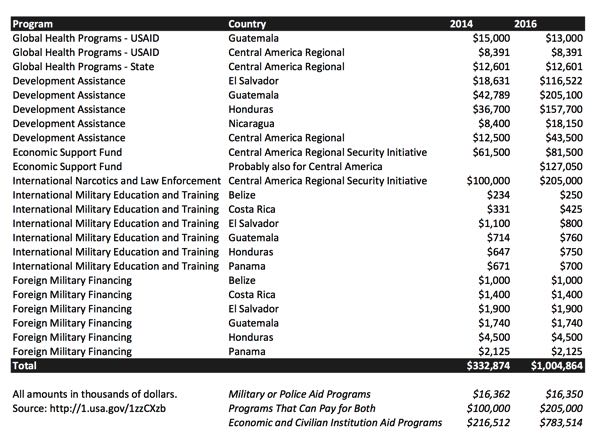

Here is how the aid request breaks down. Some figures are approximate—details about the aid proposal are still not very granular—but are unlikely to be off by more than 1 percent.

Let’s walk through each aid program.

Development Assistance (DA)

This program sees the sharpest increase, making up more than half of the proposed aid package all by itself. Administered by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), DA funds anti-poverty, economic growth, and institution-building programs.

According to the aid request and a fact sheet from the Vice President’s Office, much DA would aim to improve the business climate for private-sector job creation in Central America. Priorities include trade promotion aid, energy development, literacy and vocational education, job programs for at-risk youth, and improvements to governments’ provision of basic services. It will be critical that private-sector “job-creation” aid in this category truly reaches the most vulnerable populations, rather than benefiting elites without trickling down.

Economic Support Fund (ESF)

Also administered by USAID, ESF is a more flexible economic aid program, allowing for assistance in amounts that cannot be justified for development purposes alone. ESF has funded a portion of the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), a series of programs that, since 2008, have sought to address the region’s citizen security crisis. (CARSI’s impact has been small: in 2014 its $161 million were spread across dozens of programs in seven Central American countries.) The aid request would assign about 20 percent of resources to ESF, tripling this account over 2014 levels.

This is our fuzziest estimate: the aid proposal’s narrative suggests that nearly all of the account’s greatly increased “Western Hemisphere Regional” fund would go to Central America, but the corresponding table does not fully specify that.

ESF would support “rule of law institutions to better administer justice, ensure due process, and protect human rights,” and “support regional economic growth assistance to improve income opportunities.” This aid account would pay for community-level violence prevention programs, including “working with faith-based organizations to provide at-risk youth with life skills, job training, and recreation activities; supporting civic groups to reclaim gang-controlled public spaces and improve basic infrastructure, such as street lights; and providing services at domestic violence assistance centers.”

Global Health Programs

A smaller amount of economic aid would go through separate child and maternal health and disease-prevention programs administered by the State Department and USAID. This amount is largely unchanged from 2014.

International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INCLE)

Carried out by the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, INCLE is the only program that can pay for both military/police and economic/institution-building aid. It has made up the majority of CARSI, paying for efforts ranging from vetted anti-drug units and model community police precincts to civilian judicial reform and anti-corruption programs.

The 2016 proposal would more than double INCLE assistance. No public accounting currently exists of how this program is distributing resources across countries, or across its disparate range of priorities.

The aid request explains that INCLE would pay for an “extension of Model Police Precincts; in-service training and capacity enhancements of law enforcement personnel including anti-gang and transnational crime task forces; strengthening security and justice institutions to address transnational crime through joint police-prosecutor task forces; land border and maritime interdiction; regional aviation; and efforts to combat impunity. Increased emphasis will also be given to activities that support civil society through access to justice, protection of human rights, anticorruption, community engagement and support to justice system actors, with a particular focus on programs that address the insecurity and lack of opportunity driving increased migration.”

Foreign Military Financing (FMF)

The principal military assistance program in the foreign aid budget, State Department-administered FMF has gone principally to Central American military units that operate in coastal, river, and border regions.

The 2016 aid request would hold FMF for Central America at 2014 levels.

The aid request explains that FMF will “support partner efforts to control national territory and borders,” as well as “security sector reform to ensure that at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels each country has the ability to manage, plan and carry out their border and maritime missions in the most effective manner to counter TCOs [transnational criminal organizations].”

International Military Education and Training (IMET)

Administered by the State Department, IMET funds training courses for foreign militaries. This relatively small program would not grow in the 2016 request. The aid request lists Honduras, along with Colombia and Mexico, as a priority country for the IMET program in the Western Hemisphere. El Salvador is the only country that would see less IMET assistance in 2016, a modest cut of $300,000; the document does not explain why.

Aid in Addition to the Request

The foreign aid budget includes other, smaller programs for which the 2016 aid request does not yet supply aid amounts for Central America. These include Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs (NADR), USAID’s Transition Initiatives (OTI), Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA), the Inter-American Foundation (IAF), and others.

El Salvador and Honduras are also receiving generous grants of economic assistance from the Millennium Challenge Corporation, an aid program begun during the Bush administration.

Much additional military aid flows through the Defense budget. The main program channeling military and police aid to Central America is the Pentagon’s authority to use its counter-drug budget to provide certain assistance to foreign security forces.

Congress does not require the Defense Department to provide any estimate of how it plans to spend such funds in 2016. But from two required reports to Congress, we know that $33.7 million went to Central American nations in 2013, and $9.7 million in the first half of 2014.

This paid for training, construction at military and police bases, intelligence, and equipment upgrades. Significant recent examples include coastal drug-interdiction bases for the Honduran Navy and the creation of army-police-prosecutor task forces, “Tecún Umán” and “Chortí,” operating along Guatemala’s borders with Mexico and Honduras.

Approval Will Take Several Months

These programs will continue into 2016 regardless of whether Congress approves the Obama administration’s $1 billion request. It is unclear how the new aid package will fare once it goes to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, then both full chambers, over the spring and summer as part of the annual State Department and Foreign Operations budget appropriation.

WOLA encourages Congress to fund the full amount, at the current proportions between aid programs. More details are pending, and WOLA encourages Congress to ensure that U.S. programs are carefully targeted and focus on those governments and agencies that are genuinely committed to fighting the corruption and impunity that undermine state institutions. Overall, though, this budget request appears to be a thoughtful approach that directly confronts the circumstances that have compelled so many Central Americans to leave their homeland.

The following table brings together all Central America assistance in the State Department’s “2016 Congressional Budget Justification for Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs,” released February 2, 2015.