The unprecedented pause and potential elimination of many U.S. foreign assistance programs, announced in President Trump’s executive order “Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid,” has caused shock waves worldwide. The State Department has since backtracked and taken the welcome move to exclude “life-saving humanitarian assistance” from this freeze. Still, most programs remain on long-term hold even though they support priorities that the Trump administration claims to uphold, like curbing mass migration, reducing illicit drug supplies, and fostering economic prosperity.

State Department and USAID-managed foreign assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean totaled a little over $2 billion in FY 2023, the most recent year for which an actual amount is available. While this is a fraction of the $45 billion in base U.S. foreign assistance obligated for State and USAID programs that year, it is enough to guarantee that great harm will result from the 90-day pause in use of funds and the possibility that agreed-upon programs might be modified or discontinued. That is causing great uncertainty and alarm among “implementing partners”—civil society organizations, international organizations, and contractors region-wide- : they are being forced to cancel events, lay off staff, and determine how or if they will be able to honor commitments.

The freeze applies beyond development and human rights efforts to encompass programs that groups like WOLA have often critiqued. Much U.S. military and police aid, including training programs and counter-drug eradication and interdiction funded through the State Department’s International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) Bureau, is now on hold.

Far from making the United States safer, stronger, and more prosperous, the pause in funding and uncertainty about future funds undermine fundamental U.S. interests to an extent that is difficult to comprehend. It is actively weakening efforts to address the reasons millions are fleeing Latin America and the Caribbean, like armed conflicts, violent organized crime, rampant corruption, democratic backsliding, closing civic space, weak justice systems and rule of law, inadequate policing and public security, gender-based violence, exclusion from formal markets, and vulnerability to climate change. The aid freeze is an exquisitely wrapped gift to the United States’ regional adversaries, from dictators to drug lords to human smugglers to great-power rivals like China.

Current U.S. support for Latin America and the Caribbean

According to Congressional Research Service, “Over the past decade, top U.S. funding priorities for foreign assistance in the region have included addressing the underlying drivers of migration from Central America, combating drug production and supporting peace accord implementation in Colombia, and strengthening security and the rule of law in Mexico. U.S. agencies also have prioritized programs intended to counter HIV/AIDS and instability in Haiti, address security concerns in the Caribbean, and respond to the political and humanitarian crises in Venezuela and their impact on the broader region.” FY2023 appropriations are primarily passed through the Development Assistance (DA, $663.7 million), Economic Support Funds (ESF, $523.5 million), and International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE, $584.9 million) accounts. The Inter-American Foundation, which promotes microenterprises and community development throughout the Latin American and Caribbean region, also received an additional $52 million in funds. The region also received a share of global accounts and initiatives, most notably programming from the State Department’s Population, Refugees, and Migration Bureau (PRM) that is helping millions of migrants to settle there instead of proceeding further north.

The FY2024 budget approved by Congress in March 2024 included several areas that Republican legislators have long supported, including $25 million in Cuba democracy programs, $50 million for democracy programs in Venezuela, $15 million for democracy and religious freedom programs for Nicaragua, and not less than $125 million under ESF and INCLE accounts for programs to counter the flow of fentanyl, fentanyl precursors, and other synthetic drugs into the United States, principally in Mexico. A multiple of that goes to states like Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Costa Rica to counter the production and transshipment of cocaine. $70 million was appropriated to support “programs to reduce violence against women and girls, including for Indigenous women and girls” in Central America. At least $12.5 million seeks to combat human trafficking. Much of the $134.5 million in INCLE and NADR (Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs) funding for Central America seeks to dismantle and protect people from gangs while fortifying borders.

The U.S. Constitution empowers Congress to establish the federal budget. This is deeply settled law. While the executive branch has some discretion to reallocate funding within accounts, this does not mean full reversals of congressional intent, which would be a harmful precedent. “Faithful execution of the law does not permit the President to substitute his own policy priorities for those that Congress has enacted into law,” the Government Accountability Office has ruled. “The Constitution grants the President no unilateral authority to withhold funds from obligation.” In 1969, then-Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist—whom Republican presidents would go on to name to the Supreme Court as associate justice and chief justice—found that the “existence of such a broad power” to impound funds is “supported by neither reason nor precedent.” That language was upheld by a 1998 memorandum from the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel interpreting the Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

For over five decades, WOLA has advocated for a U.S. foreign policy, including assistance, that promotes human rights, citizen security, democracy, access to protection, and the rule of law. At the same time, we have opposed certain forms of U.S. assistance, particularly military assistance through the Departments of Defense and State, which backed military dictatorships; supported security-force units that engage in abuse, corruption, or support of paramilitaries and death squads; or distorted civil-military relations by, for instance, helping armed forces to take on what should be internal civilian roles. We have advocated for conditions on U.S. assistance to ensure that U.S. tax dollars do not go to security forces that violate human rights with impunity.

In a context of shrinking financial support in Latin America for human rights and democracy promotion, U.S. foreign assistance—particularly through USAID—has become a vital way for civil society partners throughout the region to continue with their work. Below, WOLA lays out some of the main impacts that even a pause—let alone an elimination—of U.S. cooperation represents for Latin America.

Mexico

Much recent U.S. assistance to Mexico has focused on strengthening the rule of law and addressing crime, with the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) working to build capacity in Mexican security and justice institutions. As the current funding pause halts State Department programs to combat transnational crime, it is paradoxically freezing and threatening to defund U.S. engagement on some of the very issues the current administration identifies as key to improving not just Mexico’s security, but that of the United States.

Just since Inauguration Day, the Department of Justice (DOJ) issued a statement about how extensive U.S.-Mexico cooperation resulted in Mexico’s arrest of the leader and another member of “a prolific transnational drug trafficking organization operating along the U.S.-Mexico border.” The statement commented on how funding through INL had enabled DOJ to provide valuable assistance—assistance that is among the categories currently “paused.”

For its part, USAID has provided important support for Mexican institutions’ efforts to address the country’s devastating disappearance crisis, as well as assistance that aims to improve human rights, protect journalists and human rights defenders, and support economic development and state-level justice institutions. Cutting off such programs would not only harm people and groups in Mexico, but could undermine the current administration’s focus on migration, weakening efforts to address the root causes of why people migrate, like crime and insecurity.

Central America

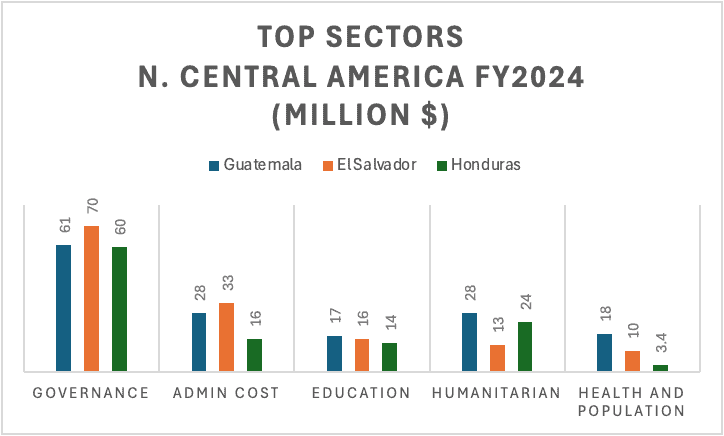

Under the U.S. Strategy for Addressing the Root Causes of Migration and through different agencies, particularly USAID, Central American civil society organizations, international organizations, and others working with government institutions are able to address economic insecurity; combat corruption, strengthen democratic governance, advance the rule of law, and promote respect for human rights, labor rights, and a free press. Due to irregular migration, poverty, violent crime, lack of good governance, and anti-democratic practices, the region’s northern countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) rank among the U.S. government’s top-priority countries for assistance in the Western Hemisphere.

As in Mexico, the pause and potential elimination of funding may undermine the very foreign policy objective—reducing migration to the U.S.—that the Trump administration has declared to be its top priority in the Americas. In 2019, when President Trump decided to freeze and reprogram $450 million in U.S. foreign aid to Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, the social and humanitarian effects harmed U.S. interests. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the cuts affected “65 of the State Department’s 168 projects, and 92 of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s 114 projects”; in Honduras, for instance USAID had to cancel an $8 million project that was reducing criminal recidivism among at-risk youth.

In Guatemala, the most impacted project will be Justice and Transparency, which aims to “reduce criminal impunity and more effectively investigate, prosecute, and adjudicate crimes that drive illegal migration”. Given the country’s lack of judicial independence and criminalization of dissident voices, freezing this program could prevent elected President Bernardo Arévalo and civil society organizations from denouncing irregularities in the troubled judiciary and restoring the rule of law. In El Salvador, good governance initiatives, which seek to “support avenues for meaningful public participation and oversight, as well as for substantive separation of powers through institutional checks and balances,” will grind to a halt in a context of deteriorating democratic values and human rights. In Honduras, measures to improve government’s transparency, accountability, and citizen-responsiveness will be affected during the crucial runup to the November 2025 general elections.

Venezuela

The assistance freeze puts at serious risk the situation of civil society and the preservation of civic space as Venezuela’s political context continues to worsen. It comes at a time when the Venezuelan regime has enacted a law that hinders NGOs’ capacity to operate, specifically criminalizing those civic organizations and independent media outlets that receive foreign funding, in particular from the United States. At this crucial moment, stalling funding “for democracy programs” allocated by Congress ultimately favors Maduro and undermines the Trump’s administration’s stated priorities.

Venezuela has a human rights and humanitarian crisis with broad regional implications: a quarter of its population has left the country in the past decade, with 85 percent of them relocating elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean. Not only is the aid freeze impacting efforts related to the exercise of democratic freedoms and reporting on conditions in Venezuela, but it is also holding up a large amount of funding destined to provide humanitarian assistance to Venezuelans inside and outside the country with integration efforts, food, health, livelihood, protection, nutrition, sanitation, and water. From FY2017 to FY2024, the U.S. government provided over $3.5 billion in humanitarian aid to Venezuela and countries sheltering Venezuelans. From FY2017 to FY2024, U.S. democracy, development, and health assistance allocated from annual appropriations for Venezuela totaled around $336.2 million.

These efforts, currently on hold, have been helping to reduce Venezuelan migration through the Darién Gap and toward the United States. Many who might otherwise continue migrating are now benefiting from more humane conditions and integration efforts where they are, both in Venezuela and in receiving countries throughout the hemisphere. Likewise, they are benefiting from support to maintain civic space and resist authoritarianism.

Colombia

Colombia is the United States’ top aid recipient and significant ally in the region on issues including defense, security, counter-narcotics, and migration. U.S. assistance has totaled about $14 billion this century. The United States has a preferential trade status in Colombia. Both nations collaborate closely on intelligence, corruption, combating illicit economies, and trafficking in persons.

As the world’s number one cocaine producer and the only country in the hemisphere with as many as eight active internal armed conflicts despite a peace process that ended one of them, Colombia is key to U.S. interests. Our nations have built extensive counternarcotics, counterterrorism, and security relationships. When Plan Colombia began in 2000, assistance first focused heavily on anti-narcotics and security; later, it evolved into a sophisticated package that included trade and economic development, migration, conflict resolution, building government presence, strengthening the rule of law, human rights, and environmental conservation. In the country that tops the global charts in killings of social leaders, this human rights support has been lifesaving.

Assistance to Colombia has long enjoyed bipartisan support; Republican and Democratic administrations have agreed it is necessary. USAID’s cooperation supports the country’s efforts to consolidate peace in conflict areas. It focuses explicitly on vulnerable populations disproportionately affected by violence, especially Afro-descendant, Indigenous, and rural communities. USAID efforts are crucial to advancing citizen security and reconciliation in one of the most violent and conflictive countries in the region. In one of the most biodiverse and mineral-rich countries in the world, USAID has sought to preserve Colombia’s natural resources.

Colombia also receives the largest share of the migration from Venezuela, with over 2.8 million—about 5 percent of its population—remaining within its borders. Working with the United States, Colombia has been a regional leader in efforts to share the cost of integrating migration.

Cutting foreign assistance to Colombia goes against U.S. interests in addressing migration, narcotics, and other illicit economies, transnational crime, security, and peace. It punishes its most loyal economic partner in South America, pushing it to increase relationships with rival outside powers like China. The result could be the sacrifice of a quarter-century of U.S. aid investments and the loss of a key partner in the search for solutions to the Venezuelan political and humanitarian crisis.

Counter-narcotics

WOLA has criticized the effectiveness and the human rights impact of past U.S. counter-drug efforts in the region, which have failed to reduce drug supplies because they place most emphasis on security forces and punitive measures while failing to address market dynamics and rule of law challenges. That said, we note that the aid freeze is hobbling even these programs: we are hearing reports of confusion in INCLE-supported eradication and interdiction programs and even the temporary halt of ongoing police training efforts.

The INL mission in Bogotá has reportedly been forced already to lay off 250 contractors. The freeze has also grounded dozens of Colombia’s U.S.-provided Black Hawk helicopters for at least three months, for lack of maintenance and contractor crews. The Black Hawks were the largest single item in the much-touted “Plan Colombia” aid packages of the early 2000s.

Climate

Latin America and the Caribbean as a whole has minimal historical responsibility for planet-warming emissions, but the region’s residents are highly vulnerable to climate-driven disasters that are likely to lead to increased displacement and migration. Superstorms, droughts, heatwaves, sea-level rise, and breakdowns in hydroelectric power threaten to worsen the drivers of migration.

For FY2024, Congress approved less than $1 billion of Biden’s overall climate aid request of $4.3 billion, while congressional Republicans made clear that they would prefer to virtually eliminate U.S. international climate aid, including efforts to protect the Amazon rainforest. On the first day of his new presidency, Trump’s executive order withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement also revoked the Biden administration’s international climate finance plan. Apart from ceasing support for efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the elimination of this assistance will mean less support for countries throughout the region as they contend with natural disasters, develop resilience strategies, and bolster food security, among other measures.

Regional Migration

As has been highlighted above, several Latin American countries have been strategic partners for addressing regional migration. U.S. support has been critical for reception and integration services as well as strengthening asylum systems throughout the region. In FY2023, for example, the total in the Migration and Refugee assistance obligations was $543.9 million; the majority of these funds supported the needs and integration of Venezuelan migrants and refugees who have settled throughout the region.

In part, according to the Congressional Research Service, this aid sought “to prevent migrants from abandoning their initial destinations and engaging in secondary migration toward the U.S. Southwest border.” If it fails to address the needs of host communities and support vulnerable populations applying for protection closer to home, a single-minded focus on border security and enforcement, will contribute to greater secondary migration toward the United States and worsen already difficult humanitarian situations in several countries along the migration route.

Special note goes to Haiti, where a collapse of governance and rampant gang violence has made living conditions intolerable for much of the population and continues to spur historic migration. WOLA notes with great alarm that the aid freeze is already crippling the minimal effort to bring some security to the island nation’s residents: INL-funded police advisors working with the Kenya-led Multinational Security Support mission have already been furloughed, the Miami Herald reported on January 28.

Local Impact

An informal survey distributed to WOLA partners between January 28 and 30 about the impact of the executive order on operations of Latin American human rights, humanitarian, and other civil society groups presents a grim picture of the near future. The organizations surveyed represent a broad range of issues, primarily self-identifying their missions as working with migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees; defending human rights; promoting good governance and transparency; strengthening civil society; or women’s rights.

The survey included two multiple-choice questions, with possible answers being Sí (yes), No (no), or Aún no lo sabe (don’t know yet).

As these graphics illustrate, the majority of responding organizations indicated that they will have to cut projects and reduce staffing. Some organizations said they will have to shut down their operations entirely. A vibrant civil society is needed in any healthy democracy. Apart from the impact on service provision–from defending victims of human rights violations to protecting journalists at risk to supporting Venezuelans who have fled the humanitarian crisis and human rights violations under the Maduro regime–the weakening of civil society will hamper long-term development, peace, and stability in Latin America and citizen efforts to hold governments accountable and promote democracy.

”Great Power Competition”

Many of the aid programs affected by the new administration’s freeze originated from the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961: a bipartisan initiative, at the height of the Cold War, to compete with the Soviet Union for influence and goodwill in the developing world. While Cold War competition led the U.S. government to partner with regimes that did great harm to rights and democracy—a central reason WOLA was founded in 1974—it still makes sense to partner with democratic states in order to deny access and influence to other actors that are more authoritarian and less rights-respecting than the United States.

China, with its one-party regime, curbs on basic freedoms, violent persecution of ethnic minorities, and high-tech societal surveillance model is one such authoritarian actor. China also happens to be dramatically ramping up its grants of development assistance around the region, buying goodwill and partnerships through initiatives like the Belt and Road initiative, which now has 22 signatories in Latin America and the Caribbean.

While WOLA does not endorse a “Cold War 2.0” model of tit-for-tat competition with China in the Americas—the potential is too great that it could become a pretext for backing malign regimes in the region—we note that if one uses that frame, the current aid freeze is a stunning act of unilateral disarmament. Freezing and cutting aid not only increases China’s numerical advantage: it devastates the United States’ reputation and credibility as a reliable partner in all of the development, migration, peace-building, and civil society initiatives discussed here. It will take many years to recover that credibility, years during which China and other competitors will be able to make important strategic gains.

Next Steps

U.S. foreign assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean has enjoyed bipartisan support for decades: programs have built on past lessons and become more sophisticated and cost effective. Foreign aid can be an important tool to advance U.S. foreign policy goals, including addressing the factors driving migration, supporting countries receiving migrants, refugees and asylum seekers to reduce secondary migration, developing more effective drug policies, expanding state presence in ungoverned territories, strengthening criminal justice institutions and the rule of law, and consolidating peace in Colombia.

For U.S. support to be effective, strategies must be long-term, sustainable, rooted in the realities on the ground, and working with constructive partners in governments, international agencies, and civil societies. Cutting or eliminating assistance in Latin America badly disrupts that long-term, sustainable focus. It will make the region less safe and give governments fewer tools to respond to the drivers of migration.

During Trump’s first term, Congress—including in 2017-18 when Republicans held the majority in both chambers—rejected proposed cuts to many programs. In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, U.S. assistance ranged from $1.67 billion to $1.8 billion per year between 2018-2021, on par with previous years.

At this critical moment, the Trump administration should spend U.S. foreign assistance as appropriated by Congress. Members of Congress should do everything in their power to exercise their authority in determining the budget. While the Office of Management and Budget has rescinded its January 27 memo freezing all federal grants, this is not the case for the pause on foreign assistance, which appears in an earlier executive order despite its impact on civil society organizations and others providing vital assistance worldwide.

At the same time, Congress should insist that the Administration adhere to existing law regarding the expenditure of funds. The U.S. legislature undergoes a rigorous, detailed annual appropriations process, dividing the federal budget into 12 comprehensive bills developed and negotiated by separate subcommittees. These bills are not suggestions that the President may pick and choose like items on a menu. The 1974 Impoundment Control Act affords presidents possible avenues for rescinding or deferring some forms of spending under certain conditions. But Trump’s enormously broad, preemptive pause of foreign aid goes far beyond what the law allows and what the Constitution contemplates.

The Trump administration, like each of its predecessors, undoubtedly wishes to put its stamp on U.S. foreign policy and on the priorities that guide U.S. foreign assistance programs. The new administration will have every chance to do so through Congress’s normal budgeting and appropriations legislative processes. For at least the next two years, Trump’s GOP will control both houses of Congress through which those priorities and spending bills emerge, and the new administration’s officials will have innumerable opportunities to try to make the case for changes they consider necessary. But the pre-emptive pause of vast swathes of U.S. foreign aid, without warning and without any assurances that programs will resume, has no basis in U.S. law, undermines other governments’ confidence in U.S. reliability, and is causing harm to civil society organizations that play a vital role in the life of any democratic society.